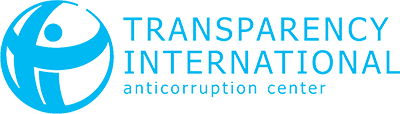

Corruption Perceptions Index 2025: Decline in leadership undermining global fight against corruption

At a time of massive Gen Z–led protests against corruption and a dangerous disregard for international norms by some governments, the 31st edition of Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index reveals a concerning picture of long-term decline in leadership to tackle corruption, alongside limited signs of progress.

Berlin, 10 February 2026 – Corruption is worsening globally, with even established democracies experiencing rising corruption amid a decline in leadership, according to Transparency International’s 2025 Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI), published today. This annual index shows that the number of countries scoring above 80 has shrunk from 12 a decade ago to just five this year.

Our data show that democracies, typically stronger on anticorruption than autocracies or flawed democracies, are experiencing a worrying decline in performance. This trend spans countries such as the United States (64), Canada (75) and New Zealand (81), to various parts of Europe, like the United Kingdom (70), France (66) and Sweden (80). Another concerning pattern is increasing restrictions by many states on freedoms of expression, association and assembly. Since 2012, 36 of the 50 countries with significant declines in CPI scores have also experienced a reduction in civic space.

2025 saw a wave of anticorruption protests led by Gen Z, mostly in countries in the bottom half of the CPI whose scores have largely stagnated or declined over the past decade. Young people in countries such as Nepal (34) and Madagascar (25) took to the streets to criticise leaders for abusing their power while failing to deliver decent public services and economic opportunity.

Transparency International is warning that the absence of bold leadership in the global fight against corruption is weakening international anticorruption action, and risks reducing pressure for reform in countries throughout the world.

François Valérian, Chair of Transparency International said:

“Corruption is not inevitable. Our research and experience as a global movement fighting corruption show there is a clear blueprint for how to hold power to account for the common good, from democratic processes and independent oversight to a free and open civil society. At a time when we’re seeing a dangerous disregard for international norms from some states, we’re calling on governments and leaders to act with integrity and live up to their responsibilities to provide a better future for people around the world.”

Transparency International is calling for:

- Renewed political leadership on anticorruption, including the full enforcement of laws, implementation of international commitments, and reforms that strengthen transparency, oversight and accountability.

- Protection of civic space, by ending attacks on journalists, NGOs, and whistleblowers, and stopping efforts to restrict independent civil society work.

- Close the secrecy loopholes that let corrupt money move across borders, including by reining in professional gatekeepers and ensuring transparency on who really owns companies, trusts and assets.

Decline in leadership against corruption

In many European countries, anti-corruption efforts have largely stalled over the past decade. Since 2012, 13 countries in western Europe and the EU have significantly declined, and only seven have significantly improved. In December 2025, the EU agreed its first Anti-Corruption Directive to harmonise criminal laws on corruption. What could have been a zero-tolerance framework was watered down by some member states, including Italy (53), which blocked the criminalisation of public officials’ abuse of office. The result: a framework that lacks ambition, clarity and enforceability.

The United States (64) sustained its downward slide to its lowest-ever score. Although 2025 developments are not yet fully reflected, actions targeting independent voices and undermining judicial independence raise serious concerns. Beyond the CPI findings, the temporary freeze and weakening of enforcement of the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act signal tolerance for corrupt business practices, while cuts to US aid for overseas civil society have weakened global anti-corruption efforts. Political leaders elsewhere have taken this as a cue to further restrict NGOs, journalists and other independent voices.

High CPI scores do not guarantee that countries are corruption-free, as several top-scoring nations enable corruption in other countries by facilitating the laundering and transfer of proceeds of corruption across borders, which the CPI does not cover. For example, Switzerland (80) and Singapore (84) are among the top scorers, but have faced scrutiny for facilitating the movement of dirty money.

Shrinking civic space undermines anticorruption efforts

In the last decade, politicised interference with the operations of NGOs has scaled up in countries such as Georgia (50), Indonesia (34) and Peru (30) where governments introduced new laws to limit access to funding, or even weaken organisations that scrutinise and criticise them. Such laws are often paired with smear campaigns and intimidation. In countries like Tunisia (39), civic space is shrinking through administrative, judicial and financial pressures that constrain NGOs, even without new restrictive laws. In these contexts, it is harder for independent journalists, civil society organisations and whistleblowers to speak out against corruption and more likely that corrupt officials can continue misusing their power. Transparency International chapters in Russia (22) and Venezuela (10) have been forced into exile due to repression of civil society.

Such restrictive environments not only silence critics and watchdogs but also create real dangers for those who dare to expose wrongdoing. Since 2012, 150 journalists covering corruption-related stories in non-conflict zones have been murdered – nearly all of these in countries with high corruption levels.

Global corruption key findings

The CPI ranks 182 countries and territories by their perceived levels of public sector corruption on a scale of zero (highly corrupt) to 100 (very clean).

The global average score stands at 42 out of 100, its lowest level in more than a decade, pointing to a concerning downward trend that will need to be monitored over time.

The vast majority of countries are failing to keep corruption under control: more than two thirds - 122 out of 180 - score under 50.

For the eighth year in a row, Denmark obtains the highest score on the index (89) and is closely followed by Finland (88) and Singapore (84).

Countries with the lowest scores overwhelmingly have severely repressed civil societies and high levels instability like South Sudan (9), Somalia (9) and Venezuela (10).

Since 2012, 50 countries have seen their scores significantly decline in the index: those which dropped the most include Türkiye (31), Hungary (40) and Nicaragua (14). They reflect a decade-long, structural weakening of integrity mechanisms, fuelled by democratic backsliding, conflict, institutional fragility, and entrenched patronage networks. These declines are sharp, enduring, and difficult to reverse, as corruption becomes systemic and deeply embedded in both political and administrative structures.

Since 2012, 31 countries have significantly improved their scores on the index: among the biggest improvers were Estonia (76), South Korea (63) and Seychelles (68). The long-term improvements in democratic countries like these reflect sustained momentum with reforms, strengthened oversight institutions and broad political consensus in favour of clean governance. Success in these areas has been attributed to among other things, digitising public services, professionalising the civil service, and embedding regional and global governance standards.

Results for Armenia and Other Countries

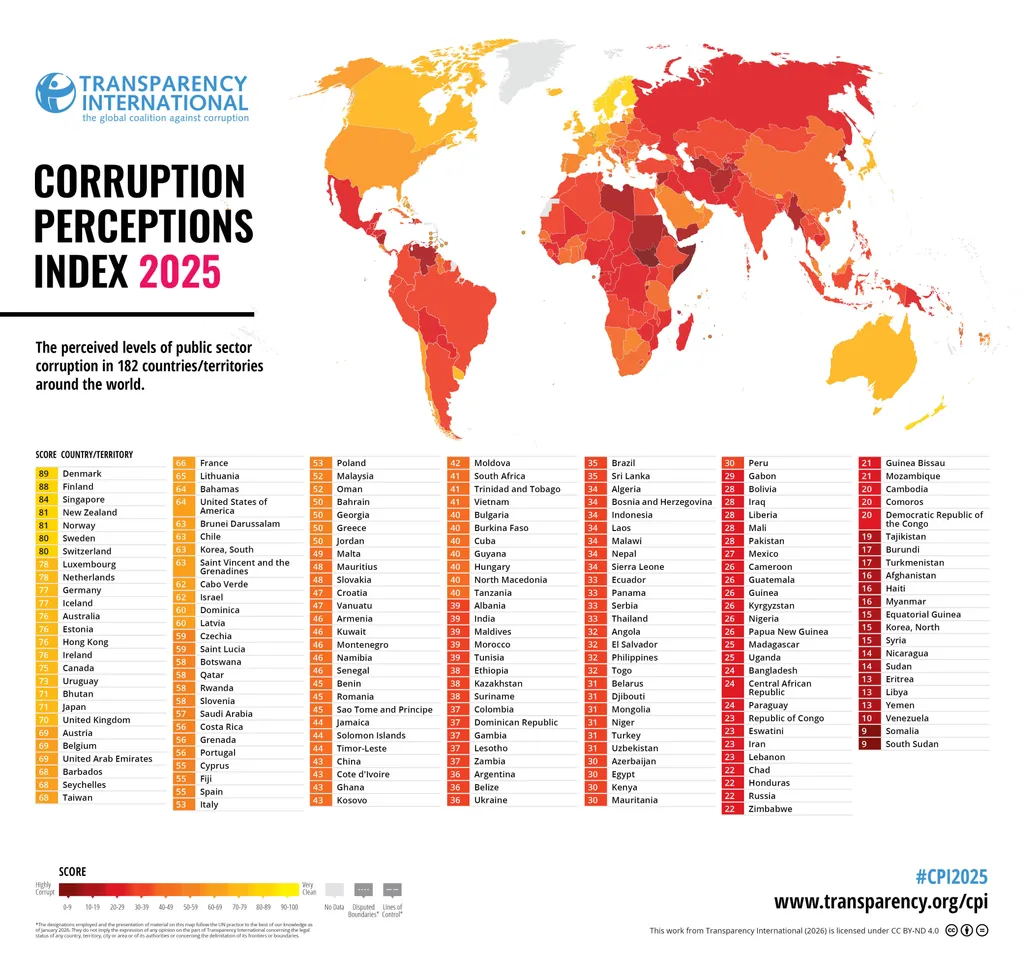

Armenia’s CPI 2025 score decreased by one point compared to the previous year, falling to 46 points on a scale from 0 (highly corrupt) to 100 (very clean).

Armenia’s CPI 2025 score (46) is the arithmetic mean of the scores from six sources used in its assessment.

These sources are:

Bertelsmann Foundation's 2026 Transformation Index (51 points, unchanged from 2024);

Freedom House’s Nations in Transit 2024 – Corruption subindex (44 points, unchanged from 2024); Global Insight Country Risk Ratings 2024 (46 points, unchanged from 2024);

Political Risk Services International Country Risk Guide 2025 (33 points, unchanged from 2024); Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Project 2025 Publication (50 points, unchanged from 2024);

World Economic Forum’s Executive Opinion Survey 2025 (53 points, compared to 56 in 2024).

Figure 1 presents Armenia’s CPI scores for the period 2015–2025.

In the CPI ranking covering 182 countries in 2025, Armenia shares 65th–69th places with Kuwait, Montenegro, Namibia, and Senegal (in 2024, Armenia shared 63rd–64th places among 180 countries).

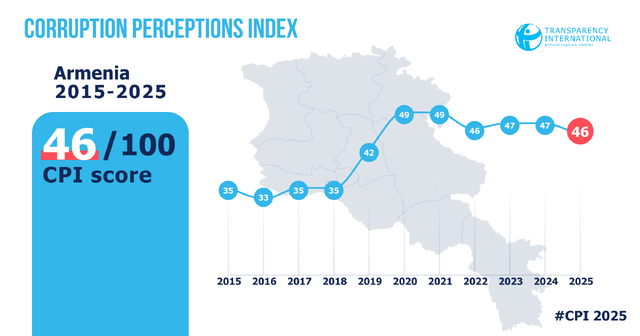

Figure 2 presents the 2025 CPI scores of the Council of Europe member states, including Armenia. As shown in the figure, among the 42 Council of Europe countries for which the CPI was calculated in 2025, Armenia, with its 2025 CPI score, shares 30th–31st places with Montenegro. Moreover, among the 27 EU member states, only three countries—Romania, Bulgaria, and Hungary—have CPI scores lower than Armenia’s.

This represents a rather modest performance, which also suggests that anticorruption reforms have not yet delivered the results expected by businesspeople and experts, whose perceptions are captured by the Corruption Perceptions Index.

As in the previous four years, Armenia’s CPI score in 2025 (46) remains higher than the global CPI average, which declined from 43 to 42, marking the lowest global average of the past decade. Armenia’s score also exceeds the 2025 CPI scores of its neighboring countries (with the exception of Georgia) as well as those of the other Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU) member states—Russia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, and Kyrgyzstan.

Among Armenia’s neighbors, Turkey (31) shares 124th–129th places, Iran (23) ranks 153rd–156th, and Azerbaijan (30) ranks 130th–134th. Among EAEU countries, Kazakhstan (38) ranks 96th–98th, Belarus (31) shares 124th–129th places, Kyrgyzstan (26) ranks 142nd–147th, and Russia (22) ranks 157th–160th.

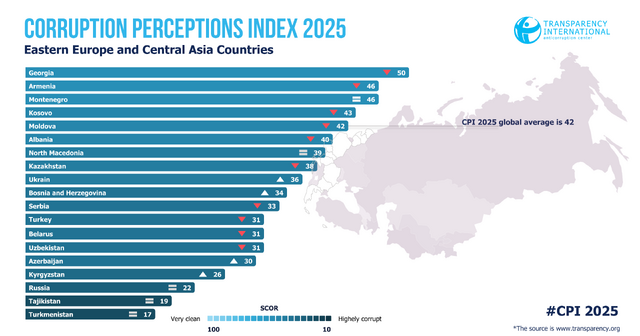

Figure 3. presents 2025 CPI scores for Eastern Europe and Central Asia region.

According to Transparency International’s regional classification, Armenia is included in the Eastern Europe and Central Asia region, whose ranking table based on CPI scores is presented in Figure 3.

As shown in the figure, Armenia ranks second among countries in the region, following Georgia (50), which ranks 53rd–55th.

About the Corruption Perceptions Index

Since its inception in 1995, the Corruption Perceptions Index has become the leading global indicator of public sector corruption. The index scores 180 countries and territories around the world based on perceptions of public sector corruption, using data from 13 external sources, including the World Bank, World Economic Forum, private risk and consulting companies, think tanks and others. The scores reflect the views of experts and business people.

The process for calculating the CPI is regularly reviewed to make sure it is as robust and coherent as possible, most recently by the European Commission's Joint Research Centre in 2017. All the CPI scores since 2012 are comparable from one year to the next. For more information, see this article: The ABCs of the CPI: How the Corruption Perceptions Index is calculated.