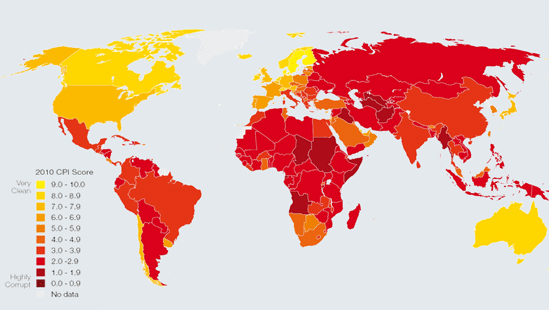

With governments committing huge sums to tackle the world's most pressing problems, from the instability of financial markets to climate change and poverty, corruption remains an obstacle to achieving much needed progress, according to Transparency International's 2010 Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI), a measure of domestic, public sector corruption released today.

The 2010 CPI shows that nearly three quarters of the 178 countries in the index score below five, on a scale from 0 (perceived to be highly corrupt) to 10 (perceived to have low levels of corruption), indicating a serious corruption problem.

"With the livelihoods of so many at stake, governments' commitments to anti-corruption, transparency and accountability must speak through their actions. Good governance is an essential part of the solution to the global policy challenges governments face today," said Huguette Labelle, Chair of Transparency International (TI).

To fully address these challenges, governments need to integrate anti-corruption measures in all spheres, from the responses to the financial crisis and climate change to commitments by the international community to eradicate poverty. For this reason TI advocates stricter implementation of the UN Convention against Corruption, the only global initiative that provides a framework for putting an end to corruption.

"We need to see more enforcement of existing rules and laws. There should be nowhere to hide for the corrupt or their money," said Labelle.

Corruption Perceptions Index 2010: The results

In the 2010 CPI, Denmark, New Zealand and Singapore tie for first place with scores of 9.3. Unstable governments, often with a legacy of conflict, continue to dominate the bottom rungs of the CPI. Afghanistan and Myanmar share second to last place with a score of 1.4 and with Somalia coming in last with a score of 1.1.

Where source surveys for individual countries remain the same, and where there is corroboration by more than half of those sources, real changes in perceptions can be ascertained. Using these criteria, it is possible to establish an improvement in scores from 2009 to 2010 for Bhutan, Chile, Ecuador, FYR Macedonia, Gambia, Haiti, Jamaica, Kuwait, and Qatar. Similarly, a decline in scores from 2009 to 2010 can be identified for the Czech Republic, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Madagascar, Niger and the United States.

Notable among decliners are some of the countries most affected by a financial crisis precipitated by transparency and integrity deficits. Among those improving, the general absence of OECD states underlines the fact that all nations need to bolster their good governance mechanisms.

As for the former communist countries, Estonia with CPI 6.5 score kept its ranking as the least corrupt former Soviet republic. By the way, this year it became a sole leader among the former communist countries as well (last year it shared the first place with Slovenia). By using the above mentioned criteria for progress or backslide, one may record that there were no essential changes in 2010 in all former Soviet countries (including Armenia), as well as in Armenia's neighbouring Turkey and Iran in 2010.

Armenia's CPI score continued its slow decrease and in 2010 it dropped by 0.1 from 2.7 to 2.6. By its score Armenia shared the rankings of 123 to 126 together with Eritrea, Madagascar and Niger (last year Armenia shared the ranking of 120 to 125).

The message is clear: across the globe, transparency and accountability are critical to restoring trust and turning back the tide of corruption. Without them, global policy solutions to many global crises are at risk.

For additional information please visit: http://www.transparency.org/policy_research/surveys_indices/cpi